Day 21 – Thursday, 18 April 2024

I have to finish this. Memories are slipping away.

I think that one reason I’ve found it harder to write these closing scenes is that one significant driver of my desire to record my experiences is noticeably lessening. Another is purely the dynamics of group travel. My diaries of New York were written during a trip by myself. If I decided to spend an evening in my hotel room, I could, without consulting any other human being. Travel companions, some of them underage and for whom one is at least nominally responsible, rob one of that freedom. I may not be hungry, but someone will be, so there is never a night off to catch up with writing.

But a more significant factor does seem to be familiarity. A week in New York was not, could not be, enough to exhaust the catalogue of ordinary absurdities that are such a terrific feature of travel – all the minor weirdnesses that make up the nearly constant amusement at the-way-they-do-things-here, contrasted with the-way-we-do-things-at-home. It might even be heightened in the United States, given the many things we have in common, from a colonial past to shared popular culture to an ever more shared dialect. When ordinary people are weird in English, it’s somehow weirder, or at least funnier, than if obviously different folk are different in their particular folk ways.

And the Japanese are different. Physically different (short, slim, usually neatly dressed) and different in their behaviour (orderly, considerate). Teenage girls aside, who will chatter away in a manner that is universal, they tend to be silent on public transport. Never once in a week on the Tokyo subway did I hear anyone on a mobile phone. The first word one must learn in Japanese is not, unlike most languages, “thank you”, but “excuse me” (すみません – sumimasen), which, until one learns the local technique of teleporting through torrents of people without causing anyone to break stride, one says fourteen times an hour. They speak a different language which they write using no less than three different orthographical systems, which they must deeply love because much of their advertising consists largely of just blocks of brightly coloured text (or cartoon images of teenage girls).

Or at least, they were different. They no longer seem so. Oh, Tokyo is unusual, but it is unusual compared not to Adelaide, but to Nara, or the Iya Valley. It is unusual because it is a city of 37 million people, not because it is a city of 37 million Japanese. I have, to an extent that surprises me, become used to them. Just how much I had acclimatised was driven home to me on my return to Australia, but that is a story for another paragraph.

As a consequence, they don’t seem so funny. Nothing here seems quite so funny. A fortnight ago, I was tickled by the nearly universal practice of draping little cloth flags over the top half of every restaurant doorway so that one must duck under, forcing one to bow to the house in a kind of choreographed politeness, by their habit of taking ordinary English words and simply chopping off the last bit, as if they just got bored halfway through, by the fact that one can buy bottles of whisky for nearly nothing along with a packet of cheese and fish sheets (for when you really need cheese and fish in a single product) in a konbini, that one can smoke in restaurants but not, in many places, in the street outside (the solution, apparently, is to take ten steps up onto any available flight of fire escape stairs before lighting up), at the manic obsequiousness of some retail attendants, who bob and grovel in a manner that suggests a neurological condition, at the peculiar nasal intonation adopted by many – especially bus drivers – when addressing a captive crowd. All of this and much more has driven a grin, time and again, but the frequency is, without doubt, much reduced. They are becoming normal.

So enough, for the time being, about Japan and the Japanese, because this is not just my first visit (and that of the boys, of course) to Tokyo. It is also a homecoming of sorts, for Annabelle, to the city in which she spent fourteen or fifteen not always happy months in her early twenties. Those months were, in some ways, formative. Some of the scratches she picked up then can still be seen in her paintwork, when the light shines a certain way. Here, she will reconnect with that past in a manner impossible from a distance. So I am here also to observe Annabelle-in-Tokyo, and to see if being here effects any changes to Annabelle-everywhere-else.

Part one, on our first morning in Tokyo, is Hiyoshi, what looks like a dormitory suburb halfway to Yokohama, where Anna spent some time in a small flat. Already, one part of Annabelle-in-Tokyo, or at least Annabelle-the-former-Tokyoite, is in evidence. Eschewing the advice of Maps, she wants to travel by muscle memory, jumping on the train she knows will take her there as it has taken her there many times before. This works perfectly this morning, but I make a mental note to start working out how to incorporate into our later travels the use of subway lines built since the early nineties, without giving the impression that I trust Google more than my darling wife’s thirty-year-old memories and instincts. Piece of cake.

We find the flat. We also find Keio University and, on the train, several dozen Keio University students, predominantly male, all dressed the same, all well behaved. Anna explains to Raf that it’s a major institution and he gets the idea of looking up the computer club. We have, after all, come to meet Japanese people, and his are around here somewhere. His reaching out will bear fruit, at a different institution, a little later.

We find Anna’s flat and some locals she can ask about the neighbourhood. They turn out to be Taiwanese immigrants, obviously not rich, so the area is apparently still supplying affordable residential solutions for foreigners of limited means, just as it did thirty years before. Photos are taken, but we don’t knock on the door, held back by an unnecessary diffidence.

Once again, the Japanese lack of dedication to the art of caffeination shows itself. In any Australian area with a similar density of students I would expect the main street to support several coffee shops of hipsterish mien, but all we can find is a chain outlet. After a coffee there, Seb and I decide to head to Akihabara, the famous otaku haven, and go looking for manga and anime shops. It’s moderately disappointing, with little of interest save for my first real sight of “maids” – girls in lolicon costumes on the street, spruiking retail outlets of various types. Being more interested in trading card games shops than mildly sexualised tourist traps, we press on. We do find a couple of games shops but it turns out that no major bargains are to be found. The box games are just as expensive as in Adelaide and, of course, are largely in Japanese. After a couple of hours and a katsu curry, we’re ready to rejoin Anna and Raf, who spent the time exploring the Keio U campus. Raf fails to find any fellow geeks.

Back in Roppongi, we track down the building where Anna used to work as a receptionist in a school for beauticians. She goes inside, but can’t find anyone who remembers the olden days. Before we found them, she and Raf had also visited Asahi TV, where she also used to work. Anna had asked if they had any broadcast archives dating from her time on screen. Nobody could help there, either, although she came away with a couple of phone numbers she might be able to try. I don’t think she ever does.

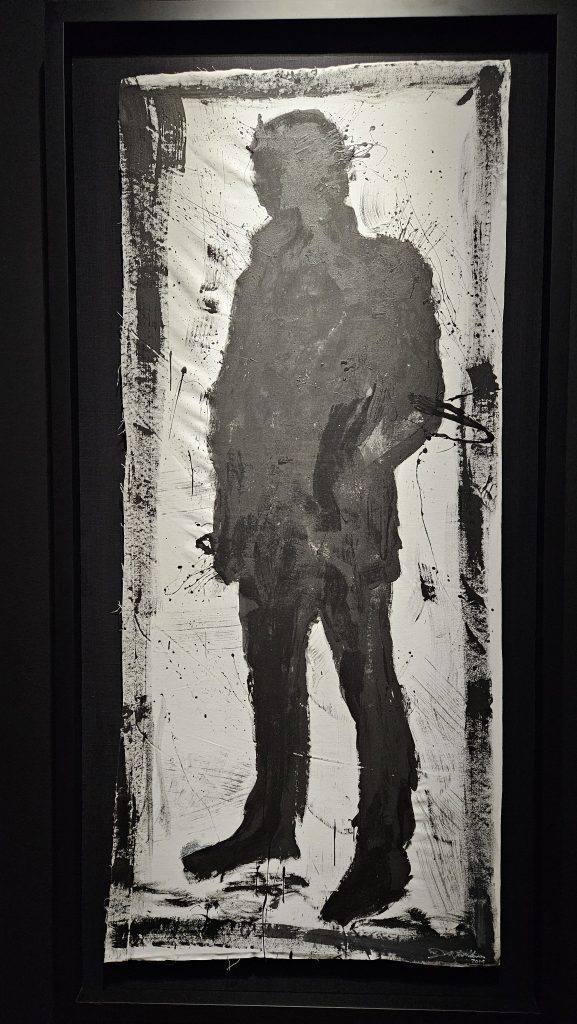

Before we leave, we drop into the Mori Art Museum for an excellent exhibition of works by famous urban artists, Banksy the most famous of the lot. It’s the first time I’ve seen his work other than the well known murals, and they’re impressive, as is the work by Richard Hambleton, the Shadowman, with whom I wasn’t previously familiar. A busy day and a good one.

Leave a Reply