Monday, 19 December 2022

Into London, my only full day so to do. Steven found enough time to join me for a few hours in a schedule filled with attempts to get professional commitments out of the way so that the family could enjoy the Christmas season without such distractions and, of course, dealing with those distractions already, the girls having been off school since the end of the previous week. There’s a performance of the pantomime almost every day, for a start, and while Agnes’s role is confined to one or two evenings as part of the junior class, Stella alternates between the chorus and Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother, somewhere near the top of the bill. So there’s running around to do aplenty.

But we have the morning, and so to town, popping up near Charing Cross Road where the bookshop at which Anna worked when she was a Londoner once was. Our destination is the National Gallery, which has a whole-of-life exhibition of Lucian Freud, one of many visual art A-listers about whom I know about two and a half biographical facts, maybe three vaguely remembered images from the Best Of catalogue and precisely fuck all else, not even the perhaps obvious-when-you-think-about-it that the surname is no coincidence, he was Sigmund’s grandson. And, as Steven points out, practically everyone within a seven iron of him on that particular family tree has their own bloody Wikipedia page. Neither the Fryer nor Yeoman families having yet set the intellectual life of Europe afire for three generations in a row, we went in with suitably humble mien.

The work was, of course, remarkable and affecting, but I will leave the reader to search for a suitable opportunity to experience the works (or reproductions) and find for herself what appreciation she may. Perhaps the most engaging aspect of the morning for me was the opportunity, never before found, to explore a visual artist with a fellow appreciator with the time and patience to speak to me of the experience as a person with fully functioning colour vision. And Freud is an artist with whom to do so (as are, no doubt, many others). Where the explanatory paragraph spoke of swirling colours, but I saw monochrome, I could ask, and know that I had an interlocutor who understood, and would take the time to lend me his eyes. Where the planes and angles of a face were brought into existence by the use of what to me seemed like kaleidoscopic hyperreality, I could ask, and colour my own experience with the words of another. It was as affecting as the works themselves. I do not, never, ever, think of myself as disabled. I think about my colour vision deficiency perhaps twice a year, as a curiosity, with no tincture of regret or self-pity. It is a fact as quotidian as the rising of the sun and it is in the forefront of my consciousness about as often. But here, in the realm of the visual arts, I know that my experience is not as that of others, and am always, save today, guideless.

I will refer here to only one work, and that for purposes other than art criticism. My hosts, perhaps drawing on reserves of self-assurance not given to us all, and certainly not to me, have installed quite an ornate full length, and breadth, mirror in the en suite bathroom adjacent my bed, right beside the shower. Getting out of the shower presents no psychological hazard, as on these winter days a temporary sheen of fog usually obscures at least the top two thirds, leaving one to face nothing more dispiriting than one’s knobbly kneecaps. But the moment before one steps under the hot water must be handled carefully, and the moment I saw Painter Working, Reflection (1993) in the National Gallery I was transported back across the hours to that morning’s ablutions. Now, a reasonable immediate response to that work is to note that the artist was in fact in reasonable shape, for a man in his early seventies, but such a thought is little comfort to a man in his early fifties, especially when contemplating those features that might fairly suffer from comparison. Still, with proper lighting and a sympathetic interpreter, perhaps I, too, could carry off an outfit consisting only of shoes and a palette knife with the same panache.

Covent Garden next, for the real mission of the trip, professionalism be damned. Anna wants a ring, and I have failed in New York, partly due to covid. Partly also because I am paralysed at the prospect of entering a jeweller anywhere, perfectly convinced that I will point at something, suffer through five minutes of blather, finally summon the courage to ask how much and be so brainsnotted by the answer that I will slither from the shop on my belly. Here, though, I have another guide in Louisa, who has, the night before, googled with me and found some boutiques of the niche that still supplies oxygen for the use of peasants and even a style or two to get me started. Armed with the links thus supplied, it only takes an hour shuttling between two venues in the Seven Dials to discover that the piece I (and Steven) decided was elegant and understated was not available in Anna’s size, at least not within the timeframe within which I’m working, and thus to settle on a second piece of a more organic feel (and thus, very possibly, a better fit for the recipient). It having been purchased, the dread of having to shop for the thing is replaced immediately by the dread of having chosen poorly, but I am getting better, in my middle age, at not being nagged at by the things I cannot change.

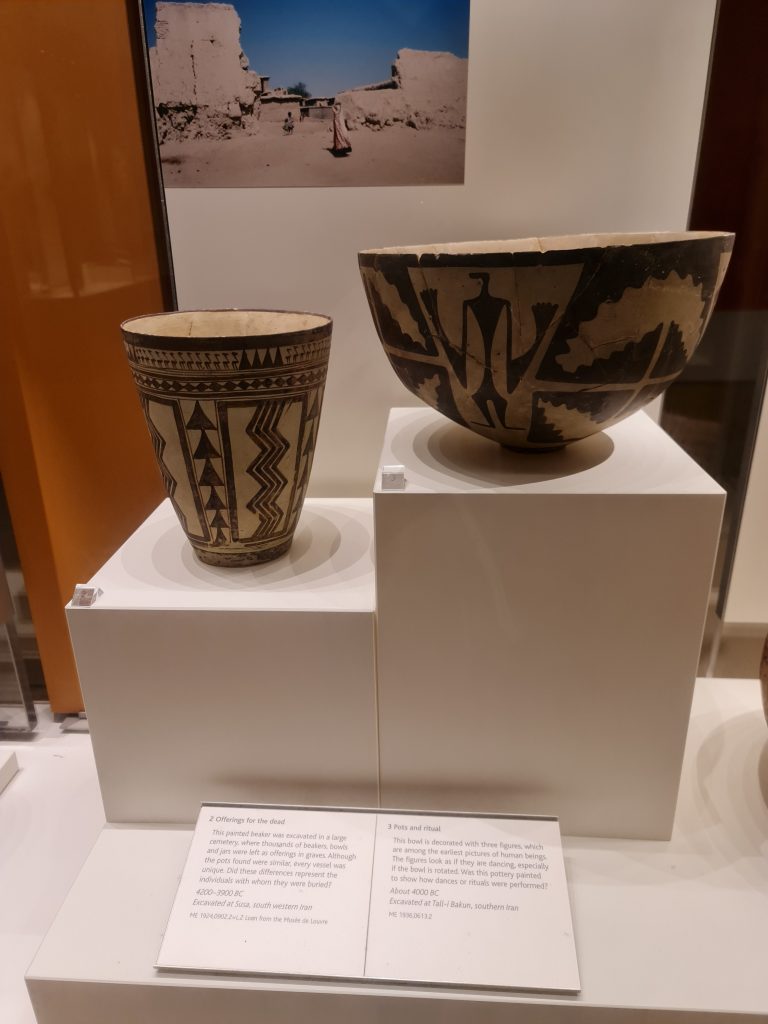

By now, Steven has headed homewards, so unaccompanied I do the one thing I knew I wanted to do as soon as I knew that I would be in London again, and went to the British Museum to go back in time, and to touch for a moment the minds of people whose lives were done before English was a language, even before Roman was an alphabet. To people, in some cases, for whom Julius Caesar was as far in the future as AD 6000 is as I type, but who wrought with skill, and for beauty’s sake alone, such works as are worth a millennium’s fame, or six.

Back to my temporary lodgings on the new Elizabeth line, now running all the way to Reading, and then out for an evening in Windsor Great Park of lights and fairies and magic and drizzle. Solid, soaking drizzle that saturates the trousers, but the light display is very pretty, similar to (though, dare I say, less impressive than) the Illuminate Adelaide event we attended in the Botanic Gardens during the last festival season, the venison burger enjoyably fattening and the carousel a delight for the daughter of my hosts for whom it, and, one suspects, everything else, cannot go fast enough.

Leave a Reply